We live in the time of a “Meaning Crisis”, when people are rapidly discarding old worldviews and adopting new ones in search of a map for navigating life. This a time of upheaval, plagued by nihilism, confusion, and many spiritual dead-ends.

The Meaning Crisis is powerful fertilizer for new social movements. One such movement is a cohort of young people newly interested in Christianity, organized on various internet platforms. At the same time, we live in the rising tide of a second Psychedelic Renaissance. Many seekers find themselves in both camps, particularly the disciples of Jordan Peterson’s remarkably successful campaign of accidental internet evangelism.

But these two traditions have deep contradictions. The lifestyle advocated by Christianity and Psychedelia could hardly be more different. For this movement of young meaning-makers to succeed, it needs to find a way to harmonize these apparently dissonant traditions.

Psychedelic culture dismisses organized religion, but psychedelic folk-wisdom has a consistent pattern of beliefs that forms a religion of its own. In my experience, there is a set of metaphysical claims and lifestyle advice shared throughout the psychedelic tribe. There is even something of a liturgical calendar — with events such as Bicycle Day, 4/20, and Shulgin’s Birthday. Some flawed attempts exist at synthesis between Psychedelic religion and Christian values, but few people have the necessary experience with both to provide a meaningful critique of these efforts and propose promising paths forward.

A Christian response to the psychedelic movement must be steeped in the patristic tradition - the subtle, beautiful, and mystical writings of first-millennium theologians. More recent denominations of Christianity have devolved, losing the vocabulary to grapple with metaphysical claims.

Like complex Baroque architecture giving way to flat modernism, much of modern Christianity is relentlessly contemporary and lacking in detail. It cannot say what it believes about metaphysical questions, and prefers to avoid them. When seekers discover these shallow and popular expressions of Christianity, they fail to find serious engagement with the ideas that are presented within Psychedelic circles. Often they leave the church in disappointment.

Psychedelics offer an undeniably compelling spiritual experience. Most pastors would rather ignore the new psychedelic culture. But eventually the psychedelic tide will flood in the doors of every little church in the hinterlands. I’m afraid that the already overwhelmed clergy of the world will be taken by surprise. If they haven’t already, in the next decade your adventurous young parishioners will be using LSD to inform their theological outlook. Be warned.

But Christians do not have to be afraid to contend with Psychedelic theology. When we examine the ideas of the Psychedelic religion and compare them to Christianity, we find that the Christian ideas are more powerful and satisfying.

The Perennialism false-start

The easiest way to resolve the tensions between Christianity and the Psychedelic religion is to ignore them. In a psychedelic trip, boundaries are blurred. The claim “these two things that appear different, are actually the same” passes as deep wisdom within the psychedelic tribe. The fancy word for this idea is “Perennialism”, the idea that all religions are really the same under the hood.

Perennialism is the most popular position among existing communities of Psychedelic Christians on the internet. It avoids the tension of contradiction and the rigor of evaluating competing truth claims. Perennialism keeps things chill, man.

But no matter how high a person gets, the logical and physical laws of the universe still apply. I’ve made the acquaintance of daring psychonauts who have taken truly epic doses of LSD to see if they could break universal laws. But they all admitted defeat. They were not able to make objects appear at will, levitate, cause logical contradictions to occur, or do anything else that would challenge our sober concepts of reality. The psychedelic state changes perception in beautiful and useful ways, but it does not change what is true.

To weigh the claim of Perennialism, we need to first make explicit the claims of the psychedelic religion and then see if there are any claims of Christianity that contradict them. Here are some commonly held beliefs among the Psychedelic tribe:

Monism - All are one

Pantheism - All is God

No Self - The self is an illusion

Moral Relativism - There is no distinction between Good and Evil

Radical Authenticity - Following your “deepest desires” towards the “true self” is a good way to navigate life

These ideas are imports from Eastern religions, primarily Hinduism, which became popular in the West at about the same time as the first wave of psychedelic renaissance. A Christianity that incorporated these ideas would be no Christianity at all. At the very least, it would be divorced from the living tradition of Christian belief and practice.

Take for example the fourth and fifth points, moral relativism and radical authenticity. These create a life path that is the polar opposite of the path of simple living, conquering the passions, and self-sacrifice laid out in the Christian New Testament. Indeed, Christian Perennialists usually dismiss the moral instructions of St. Paul and selectively edit the sayings of Jesus. This is in stark contrast to the committed Christian, who finds a fractal, self-reinforcing truth in the whole of the Christian tradition. It hangs together as a delicate ornament, each indispensable piece testifying to the beauty of the other.

But the first three points (monism, pantheism, and no-self) are the key to distinguishing between the Psychedelic worldview and the Christian worldview. They answer the questions:

What am I?

What is Ultimate Reality?

What is the boundary between self and other?

People tend to seek answers to these questions in religion and spirituality because the answers given by the dominant secular materialism are unsatisfactory — often leading to nihilism, depression and suicidal ideation. But the answers of each spiritual tradition are different from each other and some may be better than others. Let’s examine in detail the differences between Psychedelia and Christianity on these ontological questions.

Jesus is not a Hindu

As I mentioned, Psychedelic religion is a grab bag of ideas from Hinduism and Buddhism. So I may use “Eastern religion” and Psychedelia as partial synonyms.

What am I?

Let’s start our analysis with the first question listed above: “What am I?”. Psychedelics and Eastern religion answer by taking the path of deconstruction: the Self is an illusion. You are not really real. The things that you associate with your sense of existing in the world (physical feelings, thoughts, memories, desires) are just phenomena that are witnessed by awareness like any other phenomenon. If there can be said to be any real existence of the self, it is the pure awareness that witnesses the world separated from any personality, emotion, desire, or thought.

This answer can be soothing in times of suffering. If the “I” that is experiencing suffering is not real, then the suffering isn’t as real or tragic as it seems. But it can also lead to depersonalization, demotivation, and other negative consequences.

In contrast, Christians believe that you are real. The technical term for personhood in Christian theology is “hypostasis”. Each human being is a hypostasis, as are the three persons of the trinity. Each person is unique, valuable, and different from every other person that has ever existed. The self comes into being in the mother’s womb and continues for all eternity. You experience being yourself as an entity with certain traits because that is a true description of reality.

This core difference sets off Christianity and the Eastern religions on radically divergent spiritual paths. For Psychedelia and the Eastern religions, the spiritual path begins with unraveling the sense of self. For Christians, it begins by cooperating with the will of God to be the best selves we can be.

There is no reconciling these two worldviews. This distinction serves as a fork in the road for those tempted by both paths. Fundamentally, deep down, do you believe in your own existence?

What is Ultimate Reality?

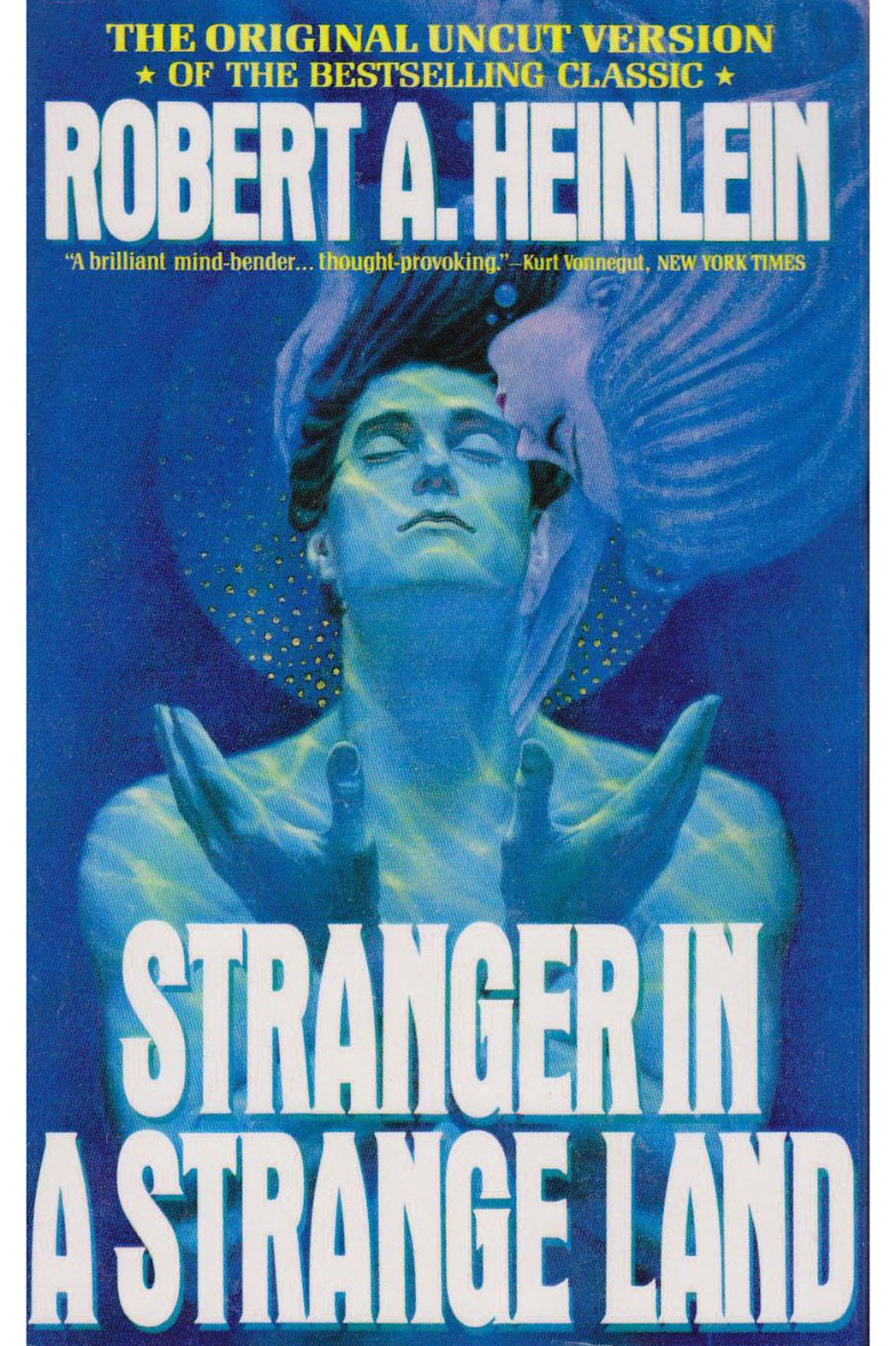

In the classic Psychedelic sci-fi novel “A Stranger in a Strange Land”, the protagonist Michael Valentine Smith becomes the guru of a utopian underground sex cult that clashes with conventional society. His followers adopt the phrase “thou art God” as a greeting and calling card.

Today, it is not uncommon in Psychedelic circles to hear someone say that you are God and that they are God. In fact, the most common belief is Pantheism, the idea that everything is God.

When a pantheist talks reverently about a divine “source”, he is adopting the Hindu concept of Brahman. In Hindu belief, Brahman is the ultimate reality. The self (atman) relates to Brahman like a drop of water relates to the ocean. The end goal of all life is enlightenment, which is when your drop flows back into the ocean of Brahman. Brahman is the source and creator of being. Creation and creator are made of the same stuff.

Like Brahman, the Christian God is also the creator and source of being. But the difference is that God is made of a different kind of stuff from humans. The divine essence is transcendent, unknowable, and separate from the essence of created beings like us.

An orientation towards the transcendent God is the distinct heart of Christianity. By “transcendent” I mean beyond human reach. No matter the heights of power, beauty, justice, or truth that mankind reaches, God will always be more powerful, more beautiful, more just, and more true. The Christian cannot fully comprehend God, because God is limitless and we are not.

The best a Christian mystic can do is approach God, but this approach is never-ending. Vladimir Lossky, quoting Etienne Gilson says “Lower, even if only for an instant and at a single point, the barrier between God and man […], and you have deprived the Christian mystic of his God,[…] any God who is not inaccessible he can dispense with; it is the God who is by His nature inaccessible whom he cannot do without.” (Mystical Theology p. 68, 69)

Similar to the Hindu path, the goal of the Christian life is towards union with God, a state called theosis or deification. But this kind of union is not the same as the Hindu/Psychedelic concept of a drop of water falling back into the ocean. In the Christian union, individuality is never lost and the human essence is never transformed into the divine essence. Rather we “participate in the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4), “becoming by grace what God is by nature” (St. Athanasius). An analogy church fathers have used for theosis is a sword glowing red after being thrust into a fire. It glows with the energy of the fire (divinity) without losing its existence as a sword.

For the Christian mystic, the ultimate principle of reality is good, but beyond himself, ineffable, reaching towards him as he reaches towards it in a process that can only be described as love.

Here we see another incompatibility, another fork in the road. Are you the same thing as the ultimate principle of reality? Are you God? In Christianity, we are not the same thing as God. Some people find this limit stultifying. And for others it is a relief. But it is clear that we cannot have it both ways at once.

What is the boundary between self and other?

Monism is the belief that everything is really one thing. Psychedelia is clearly a monist religion. This way of thinking was popular in the 1960s counter-culture when the first wave of Psychedelics was at its peak. Perhaps you’ve run across beliefs like this in relics from that period, such as the bizarre but beloved labels on Dr. Bronner’s soap:

Enjoy only 2 cosmetics, enough sleep and Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soap to clean body-mind-soul-spirit instantly uniting One! All-One! When half-truth is gone & we are dust, the full-truth we print, protect & teach alone lives on! Full-truth is God, it must! Help teach the whole Human race, the Moral ABC of All-One-God-Faith.

Monism naturally leads to a utopian impulse — if we remember that we are all the same, then we will dwell together in harmony. Unfortunately, it is hard to put this worldview into practice when it runs into the pragmatic difficulties of people with real differences competing with each other for status and resources. Historically, monist communes have not become utopias.

The opposite stance of monism is Dualism - the perspective that boundaries are real and absolute. This is not the Christian point of view either. Christianity is neither monist nor dualist, but winds up somewhere in the middle.

David Chapman is a Buddhist, and one of my favorite internet bloggers. His work is poorly organized across several blogs and hard to navigate, but it rewards an investment of patience. David introduced me to the importance of the conflict between monist and dualist worldviews, and how both are wrong. David points to a third way as a more correct alternative, a worldview he calls “participation”, in which boundaries are meaningful but porous.

The Christian philosophy of existence is closer to David’s model of participation than either monism or dualism. In fact, the word “participation”, along with “communion”, is used in the technical language of Christian theology to describe how two separate things share in each others’ existence — recalling St. Peter’s formula that we “participate in the divine nature”.

The Christian denial of monism and dualism is most clearly illustrated in the dogma of the Holy Trinity. It’s an odd concept for the uninitiated and there is a temptation to brush past it as theological esoterica. But it is key to understanding the Christian model of existence.

The Christians God is three persons with one essence. The three persons (hypostases) of God (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) are distinct in some real and important sense, and yet they are also one in a real and important way. Neither the sameness nor the distinction dominates, they are both necessary.

This pattern of being - oneness without losing distinction - is what Christians mean when they say “God is love”. It is key to understanding seemingly monist language in the Bible, such as when St. Paul calls us “one in Christ” (Gal 3:28) or when Jesus prays to the Father for his followers “that they may be one as we are one” (John 17:22).

The sacramental unions created by baptism and marriage mirror the pattern of existence of the Holy Trinity. Here, there is also an inseparable participation in the life of the other without erasing the individual existence of each person. And indeed some kind of mystical unity is meant to exist between humanity and all of nature (see Lossky’s Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church p. 109 - 113). The precise nature of these unions is mysterious.

The experience of being one with everything is a common phenomenon in psychedelic trips. Personally, I found this disturbing. The joy of communion with my fellow humans and with nature was spoiled by the terror of losing myself. I had no desire to be absorbed in some glorious monad. That kind of oneness is not love; it is an amoeba devouring its prey. Once I learned the Christian model of participation, it seemed to me to be a more true description of oneness as I had experienced it and also infinitely more desirable. It enabled me to experience feelings of union without the terror of annihilation.

Is there a place for Psychedelics in Christianity?

The growth of an intersection between the psychedelic tribe and the Christian church is inevitable. Some of these intersections will be predictably bad. Unscrupulous leaders will mingle psychedelics into their services, using them to confuse people and to exploit already imbalanced power dynamics.

But there will also be people who take psychedelics and become awakened to the desire for transcending the nihilist scientific paradigm. These people may find Christian explanations for what the world is like to be more satisfying than the muddled pastiche of ideas preached in the Psychedelic religion. This is an opportunity for evangelism.

Whether or not psychedelics have a place for practicing Christians I will leave for another time. Surely, most traditional denominations will reject them as the doorway to some other false religion. Hopefully I have shown that this doesn’t have to be the case. As psychedelics become more prominent in the medical field as uniquely effective treatments, and as more and more parishioners find Christ through psychedelic experiments, perhaps churches will develop the ability to speak to inquirers with psychedelic backgrounds and guide them towards God.

This is a great article! As an orthodox Christian (maybe you are too? It’s unclear) who has been a part of the psychedelic community in my teen years, and a part of the nondenominational church just a few years ago I tend to be more skeptical of psychedelics. I think they carry high risks for spiritual delusion as you mention, and I would suspect that there is a spiritual element to them that is deceptive, driving people away from God and not to Him.

But you may be right that this doesn’t preclude the possibility of therapeutic intervention- my intuition would be that lower doses are comparatively harmless. For example my aunt has done insulfated ketamine (medically prescribed) for ptsd, did not have any spirtual effects, but found great relief from being in patterns where she was obsessing about her abuser or being abused. She has also done intravenous ketamine, which is significantly more spiritually potent. I don’t know enough about her history to say whether or not that was a spirtual experience for her, but you could easily assume for many people it is.

Good stuff. Helps me build out a proper taxonomy.